In her 1912 history of Jacobean embroidery, Ada Wentworth Fitzwilliam reveals that needlework is violent, intimate, and transformative; it changes a surface by repeatedly puncturing it. “O, redeem the monotony of plain surfaces,” she writes. The needle is outside and inside, on the other side, crossing, creating and destroying at once.

Sterility implies “about to enter:” bloodstream, flesh. Edge of external and protected environments, contamination the risk when they meet.

Sterile doesn’t mean clean; it means killed. I think we are always walking this line between wanting connection and wanting to be entirely alone. I fight this troubling and wonderful sense constantly – that every being is just as real as I am, that I could be hurt or made unlike myself now at any moment. It makes me want to love everything harder and not at all, protect and destroy at once.

I’ve been reading and writing about fecal transplants lately; what we dismiss as waste is wondrous bacterial ecology with princess names: Roseburia, Akkermansia, Alistipes. Like all ecologies, it can swing our beings toward paradise or catastrophe. We’re biomes inside biomes inside biomes, always and never ourselves.

Medium: needle, thread, watercolor. The image is my attempt at fecal bacteria, which, despite their lovely names, all look much the same.

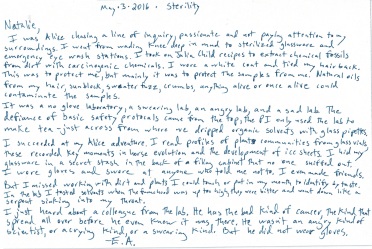

I was Alice chasing a line of inquiry down a rabbit hole, passionate and not paying attention to my surroundings. I went from wading knee deep in mud to sterilized glass ware and rooms with emergency eye wash stations. I took on Julia Child recipes to extract chemical fossils from dirt with carcinogenic chemicals. I wore white coats and tied our hair back in the lab. This was to protect ourselves, but mainly it was to protect the samples from me. Natural oils from my hair, sunblock, lotion, sweater fuzz, crumbs, anything alive or once live could contaminate the samples.

It was a no glove laboratory, a swearing laboratory, an angry lab, and a sad lab. The defiance of basic safety protocol came from the top, the principal investigator only used the lab to make her tea – just across from where we dripped organic solvents with pipettes.

I succeeded at my Alice adventure. I read profiles of plant communities from glass vials, these recorded key moments in horse evolution and the development of ice sheets. I hid my clean glassware in a secret stash in the back of a filing cabinet and no one ever sniffed it out. I wore gloves and swore at anyone who told me I shouldn’t. I even made friends.

But I missed working with dirt and plants that I could touch and put in my mouth to identify by taste. In the lab I could taste solvents when the fume hood was up too high, they were bitter and went down like a serpent sinking into my throat.

I just heard about a colleague from the lab, he has the bad kind of cancer, the kind that spreads through your body before you find out. He wasnt the swearing kind of scientist, or the crying kind, or even angry. But he didnt wear gloves.

Materials: Lab protocols and notes, water colors, sharpie.